The APS Bridge Program: Changing the Face of Physics Graduate Education

Erika E. A. Brown, The American Physical Society, College Park, MD

In 2008, the APS Board and Council released a joint statement,1 charging the APS membership with “increasing the numbers of underrepresented minorities in the pipeline, and in all professional ranks, with becoming aware of barriers to implementing this change, and with taking an active role in organizational efforts to bring about this change.”

The APS Bridge Program (APS-BP) was born out of this guiding charge. Recognizing the need for a diverse pool of high-quality domestic physicists, the APS worked to bring its unique status within the physics community to bear on the problem. In 2012, APS received a 5 year, $3 million award from the NSF, and began working to increase the number of physics PhDs awarded to underrepresented minorities (URMs: African American, Hispanic American, and Native American).

In 2015, just over 8% of bachelor’s degrees in physics were awarded to Hispanic American students,2 despite Hispanics representing almost 22% of the American college-age population. Similarly, only about 2% of physics bachelor’s degrees were awarded to African American candidates (~15% of US college-age population).3 The picture is even more dismal when one examines numbers for PhDs in physics awarded to these groups, with only 66 PhDs being awarded to URMs each year, on average.

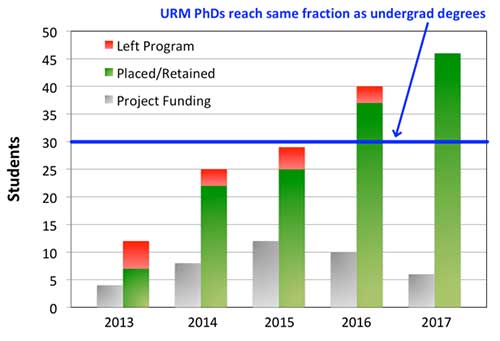

However, these small numbers present a unique opportunity: a small input has the potential to create a huge impact. If we were to increase the numbers of URM doctoral recipients by about 30 each year, we could bring the fraction of PhDs to parity with the number of BS degrees.4 We also recognized that to increase the number of students who earn PhDs, we would need to identify and share effective practices designed to help their mentors support and retain them throughout their graduate education.

The program targeted URM students who show potential for a career in physics, but for a variety of reasons have been unable to secure admissions to a graduate program through traditional applications. This allows us to reach students who would not be in graduate school without the program, and to be confident that we are truly increasing the numbers of physics graduate students.

Students submit a common graduate application, which we circulate to physics departments that we have determined to be supportive places for URM graduate students. These departments commit to providing a supportive “bridge” experience for these students. Bridge experiences generally last 1-2 years, and are often very similar to a master’s level program. Programs help students navigate the transition from undergraduate to graduate studies, with a focus on preparing students for success in a PhD program. Support is tailored to the student’s unique needs, and can take the form of additional mentoring, careful progress monitoring, thoughtful induction activities, access to advanced undergraduate and graduate level coursework to fill in knowledge gaps, and more.

The project almost immediately had many more student applications than it could ever hope to place at our (initially) funded bridge sites. So, we developed the concept of Partnership Institutions: physics departments that provide a “bridge-like experience” for students, without financial support from APS. We review applications for new Partnership Institutions semi-annually, and as of this writing, have approved 31 institutions, many of whom have taken bridge students.

To date, we have placed over 150 bridge students (and counting!) into graduate programs across the nation (See Figure 1). In 2017 alone, we were able to place 46 students into graduate programs. Once these students earn a PhD, we will have effectively erased the gap between the fraction of bachelor’s and PhD degrees awarded to URMs, a very likely event, since our retention rate is hovering around 85%.

Figure 1: Placement numbers of bridge students over life of the project. Gray bars represent the numbers of students funded by APS, while red and green bars indicate total students placed in a given year. Blue line indicates the number of additional URM doctorates needed to erase the gap between BS and PhD.

Given the program’s documented high retention rate, 5,6 we have identified effective practices used to support bridge students. Bridge sites report that these practices are not only effective for retaining bridge students, but also beneficial for all graduate students. We have compiled a number of these practices, and made them available on our website. These include a graduate student induction manual (http://www.apsbridgeprogram.org/resources/manual/) and key components of bridge programs (http://www.apsbridgeprogram.org/institutions/bridge/components/).

There were a few unexpected lessons that we learned along the way. First, we learned that aggregating applications is a quite powerful tool. Most departments are unable to spend the time required to find diverse applicants, and students are not able to submit a large number of applications due to expense. APS is uniquely situated to collect and distribute applications to interested departments. This has proved to be immensely helpful for connecting students with departments that have the ability to support them.

Secondly, we learned that admissions data are not what they seem. Although the GRE plays a big role in admissions decisions, our research has found that it may not be actually telling admissions committees what they think it is telling them. We’ve also found that student perceptions of what admissions committees are looking for in applicants differ significantly from what the admissions committees actually say they are looking for.

We found that a significant barrier to graduate school for a number of bridge students has been the expense of applications.7 Costs add up quickly when you factor in the expense of applying to each program, taking the GRE and PGRE, and sending the scores and transcripts to each school. This results in students only applying to a handful of schools, significantly reducing their chances of securing admission.

Finally, we’ve seen the importance of graduate and student groups in bringing students into the department culture, and in contributing to department events and decisions. Often, Physics Graduate Student Associations organize induction activities and provide peer mentoring to help give students what they need to succeed.

So where do we go from here? APS-BP plans to continue the most impactful components of the program: aggregating and distributing student applications to Bridge and Partnership sites, collecting and disseminating effective practices for retention, and advocating for admissions reform. We’ve also started conversations with other societies in the physical sciences, about how they might run bridge programs within their fields. Finally, we are in discussions with a number of national laboratories and industry partners about helping Bridge doctorates (the first of which we expect to be awarded in the next year) transition into their first post-graduate positions.

The APS-BP was born out of a recognized need to improve the participation of URM students in physics, as a way to diversify and strengthen the pool of domestic physicists. It has been our pleasure to have seen the impact of the program on our bridge students, and their contributions to their departments. APS-BP has enabled a number of students, who would not otherwise have had the opportunity to chase their dream of earning a doctoral degree in physics. We look forward to the important contributions these students will make to the field of physics and to the future generations of scientists they will mentor and inspire.

Erika Brown is the Program Manager for the APS Bridge Program and the APS Inclusive Graduate Education Network (IGEN) Pilot.

(Endnotes)

1 American Physical Society. “Joint Diversity Statement”. (2008). https://www.aps.org/policy/statements/08_2.cfm

2 American Physical Society. “Percentage of Bachelor's Degrees Earned by Hispanics, by Major”, IPEDS Completion Survey by Race and US Census Bureau. https://www.aps.org/programs/education/statistics/hispanicmajors.cfm

3 American Physical Society. “Percentage of Bachelor's Degrees Earned by African Americans, by Major”, IPEDS Completion Survey by Race and US Census Bureau. https://www.aps.org/programs/education/statistics/aamajors.cfm

4 APS Bridge Program. “Project Goals.” http://www.apsbridgeprogram.org/about/ProjectGoals.pdf

5 T. Hodapp and K. Woodle, “A bridge between undergraduate and doctoral degrees,” Phys. Today 70, 50 (2017).

6 T. Hodapp and E. Brown, “Making physics more inclusive”, Nature 557 (2018).

7 G. Cochran, T. Hodapp, and E. Brown, "Identifying barriers to ethnic/racial minority student's participation in graduate physics," 2017 PERC Proceedings [Cincinnati, OH, July 26 -27, 2017].

Disclaimer – The articles and opinion pieces found in this issue of the APS Forum on Education Newsletter are not peer refereed and represent solely the views of the authors and not necessarily the views of the APS.