LabEscape, or How to Use Up All One’s Available Time and Then Some, to Foster Science Outreach

“So, were we at least close to escaping?” I queried in my role as the now-deceased Watson.

“So, were we at least close to escaping?” I queried in my role as the now-deceased Watson.

by: Paul Kwiat, LabEscape Director, Professor of Physics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

“Not so much,” our host replied.

Moriarty, the archenemy of Sherlock Holmes, had won the day. And thus ended my first attempt at an escape room, this one in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Despite our failure (note to self: don’t bring 2 people to an escape room designed for 6!), I had a fabulous time and immediately determined to do better next time, and the time after that, and the time after that! I’ve now had the opportunity to partake in several such escape games (and by several, I mean 25), in the United States, Europe, and Singapore.

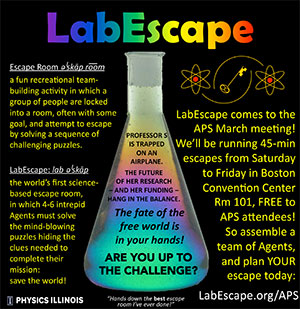

Fig. 1. a) The countdown has begun! b) A beaker filled with ordinary corn syrup becomes an art masterpiece when placed between crossed polarizers. b) The missing Professor S., played by real-life condensed matter physicist Nadya Mason.

In the last few years, a tremendous increase in the prevalence of escape games for recreation—first in Japan, then in Europe, and most recently in the U.S. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Escape_room]—is a testament to their growing popularity. A group of people are locked in a room and have exactly one hour to locate the key that will allow them to escape. However, the key is locked within a safe whose combination numbers are solutions to puzzles, whose clues in turn are hidden in other locked items, requiring other puzzles be solved, and so on. Different escape rooms provide widely varied experiences—each has its own theme, a backstory explaining the particular challenge, and its own specific puzzles. But all escape rooms have in common a time constraint and challenging puzzles, so that there is both a sense of urgency and a tremendous sense of accomplishment for each puzzle solved—and for successfully beating the game.

In reality, they aren’t actually physically locked in—or at least shouldn’t be—to prevent horrible fire accidents. After my first (non)escape, I was—obviously—immediately hooked by the immersive nature of the escape-room experience. But more than that, I had the idea that a science-based escape room would be the perfect venue to expose a larger section of the public to the joys of physics and even scientific research (more on that later). Hence was born LabEscape. Well, not quite so immediately. It took a little time to get some seedling funding (thanks to the APS and also to the University of Illinois College of Engineering for getting us started!), then more time to find and renovate a suitable space, and still more time to design, construct, re-design and re-design again the various puzzles, all the while coming up with a storyline that would be compelling and explain why people are locked up, why there are clues, why there can be hints, etc.

After a couple of months in beta-testing, LabEscape had its official grand opening on January 28, 2017. Situated in Lincoln Square Mall (one of the oldest fully enclosed malls in the country), LabEscape is one mile east of the U of I Physics building, nestled between an art boutique and a game store. We’ve now had over 4000 ‘agents’ go through, in groups of four to six people, from ages 10–~60 (sometimes it’s not polite to ask), attempting to unravel the mystery of Professor Alberta Pauline Schrödenberg.

Professor S., one of the world’s leading quantum scientists, disappeared three weeks ago, amidst growing fears that enemy agents were after her latest breakthrough in quantum computing technology, which could lead to a room-temperature quantum processor! Unfortunately, the previous agents sent in to search the Professor’s secret lab never came out again—all communication was lost after 60 minutes. Now the newest group of agents (escape-room participants) has to determine what happened to Schrödenberg and the other agents that disappeared—hopefully without disappearing themselves!

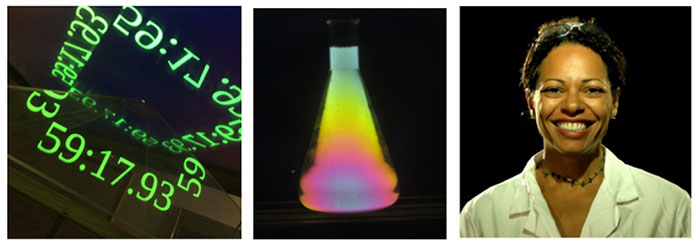

Fig. 2 a). Viewed with visible light, this odd mosaic constructed of bottle caps shows the first letter of a secret code. b) Analysis with an IR camera reveals a different letter, as does c) illumination with an ultraviolet light.

To succeed, they have to solve a series of puzzles based on physics phenomena. Fig. 2 shows one example. In their pre-briefing the agents are given some of Professor S’s class notes to look at, which cover things like polarization, light spectrum, etc., all at the junior-high or high-school level, with lots of pictures. In the course of searching the room, the agents find the bottle cap mosaic, an IR thermal imaging camera (awesome!!), and a UV light, plus a message indicating that the code they need is on the cap mosaic, in visible, low-energy and high-energy photons, respectively. Using their newly gained knowledge of the spectrum (which is also available in the room, so they don’t need to remember anything), clever agents will realize that the mosaic shows three letters depending on whether it’s looked at in the visible or IR, or with a UV light shining on it (for this puzzle we often encourage people to start with the third letter and work backwards, so they don’t get stuck with just the first two! ;-) ).

Apparently this process of solving physically interactive puzzles (as opposed to logic puzzles or riddles that form the basis of many escape room challenges) is as appealing to the general public as it is to scientists, as we’ve received nearly all 5-star reviews on various rating sites, with some people claiming that LabEscape is the best escape room they’ve ever done! We believe this is actually extremely important—our underlying goal is to improve people’s perceptions about science, so it’s critical that they have a really great time.

Our primary mission is to show people that science doesn’t need to be scary, that it can actually be fun, accessible to non-scientists, and even aesthetically beautiful (Fig. 1). By completing their mission, agents also get a taste of what scientific research is like, looking for background information, trying different approaches to solve problems, and finally getting a solution, only to find that it leads to more questions. We emphasize the importance of the three C’s: curiosity (being willing to explore, play around with things, push buttons, etc.), communication (exchanging information with fellow agents, so that everyone is clear on what information is relevant for a particular puzzle), and collaboration (both for brainstorming, but also as a good engineering strategy to reduce errors). Obviously, these same three C’s are precisely what one needs to be a successful scientist or engineer: a driving curiosity to understand the world and how to improve it, the ability to work with other researchers to solve problems too hard for any one person, and the skill to carefully record progress for the benefit of other researchers and to reach out and engage the public.

Last August, we took a portable version of LabEscape to the annual American Association of Physics Teachers conference, in Washington, D.C. Over the course of 3.5 days we had 34 runs and 187 agents attempt to complete the mission within the allotted 45 minutes. Despite not every group being successful—the success rate was about 33 percent, similar to that of non-scientists in our room back in Urbana)—everyone seemed to have a good time (see Fig. 3), so much so that LabEscape will make another road trip in just a few weeks, this time to the APS March meeting in Boston (yikes—lots to prepare before then!). If you happen to be attending the meeting, please come by and try an escape adventure (FREE to meeting attendees – you can sign up at LabEscape.org/APS). Or if you just happen to be somewhere near Central Illinois and want to try the original challenge, please visit LabEscape.org to book your own adventure.

By the summer we anticipate having had ~6000 people go through, which is probably close to ‘saturation’ for our community of 120,000. After that, we hope to relocate to a larger venue, e.g., a science museum in some metropolitan area—maybe near YOU; please contact us if you have ideas.

Fig. 3 This group of ‘agents’ at the AAPT August conference was thrilled to have escaped with their physics intuition and honor intact.