Spotlights on Outreach and Engaging the Public FOEP’s 2016 Dwight Nicholson Awards for Outreach

Questions and Answers with FOEP’s two 2016 Nicholson awardees, John M. Dudley and Joseph J. Niemela. Answers are edited for clarity as needed.

John M. Dudley, FEMTO-ST Institute and the University of Franche-Comté & Joseph J. Niemela, International Center for Theoretical Physics shared the Dwight Nicholson Award for Outreach for:

"For outstanding leadership of the International Year of Light (2015) and for optical science and engineering outreach on a global scale."

John M. Dudley,

FEMTO-ST Institute

Q. How did you get involved in outreach?

In my case, it goes right back to when I was a student in New Zealand and I ran the student Physics Society. One of the things we did was to organise the departmental Open Days, and I suppose these showed me both the need and the potential for public science communication. In a small country like New Zealand it has always been essential to justify investment in science and doing so by reaching the public is of course a very effective means. After moving to Europe I became involved in the European Physical Society, which allowed me to develop this further.

Q. What do you find most exciting about outreach? Most rewarding? Most difficult?

When things go right, outreach is its own reward — seeing young people being inspired, or watching as the lights go on in students faces as they begin to understand some new concept is something one never tires of. The difficulty — which I faced in the past but which is less of a problem now — is of course convincing skeptical colleagues of its importance and fighting against the elitism that unfortunately still seems to be present among many in physics. However, attitudes are changing albeit slowly, and one of the nicest things about the Year of Light was seeing naysayer colleagues become some of the Year’s strongest supporters. And of course there is the difficulty in combining outreach with regular academic duties and grant writing and research and travel etc etc …. I am lucky in France to be well-supported by my university and the CNRS, as well as colleagues in my department and research group otherwise I would never be able to get involved in outreach.

Q. How did you happen to be put in charge of organizing the UNESCO 2015 Year of Light?

The story of the Year of Light goes back to 2009 when I "volunteered" to represent the European Physical Society at an inter-society meeting in Baltimore to discuss international initiatives promoting optics. At the time, OSA, SPIE, IEEE and APS had joined together to promote Laserfest in 2010, but I had the feeling that there was a missed opportunity in not aiming higher for the status of an International Year (I knew of the International Year of Physics in 2005 and Astronomy in 2009). I still haven’t learned to be quiet and I said as much in the meeting, and was then "encouraged" to try to find out how to organise one (there is no manual!) which involved lots of missteps. But we decided to push ahead and in 2011 we held the "Passion for Light" launch event in Italy where Joe attended represented UNESCO-ICTP and their optics program, and it was as a result of this meeting that we really were able to push ahead. We assembled a Steering Committee with myself as Chair and Joe as Global Coordinator, and together we followed the Year through its various steps at UNESCO and the UN General Assembly to get official proclamation, to the practical implementation and the setting up of a Secretariat team in Joe’s office at ICTP.

John M. Dudley

FEMTO-ST Institute

"The difficulty — which I faced in the past but which is less of a problem now — is of course convincing skeptical colleagues of its importance and fighting against the elitism that unfortunately still seems to be present among many in physics. However, attitudes are changing albeit slowly, and one of the nicest things about the Year of Light was seeing naysayer colleagues become some of the Year’s strongest supporters."

"I am lucky in France to be well-supported by my university and the CNRS, as well as colleagues in my department and research group otherwise I would never be able to get involved in outreach."

Q. How did such a global endeavor impact you?

It’s a little obvious I suppose, but I was very struck by the many ways that students and teachers from developing countries are so passionate to learn, notwithstanding given their limited opportunities. I was also very impressed to see the new category of "social entrepreneur" developing to spread the results of science and technology to developing countries and other communities in need.

On another level, I became aware of the fact that in today’s climate, outreach is no longer optional, but is a very necessary responsibility of all scientists. And this refers not only towards the public, but also using many of the same strategies to explain what we are doing to decision-makers and politicians. I learned a lot about speaking to politicians during 2015, and it is not such an insurmountable barrier as one might think.

Q. Were there any measures made on the impact of the Year of Light? If so, what were those measures and what can be concluded by them?

Q. Were there any measures made on the impact of the Year of Light? If so, what were those measures and what can be concluded by them?

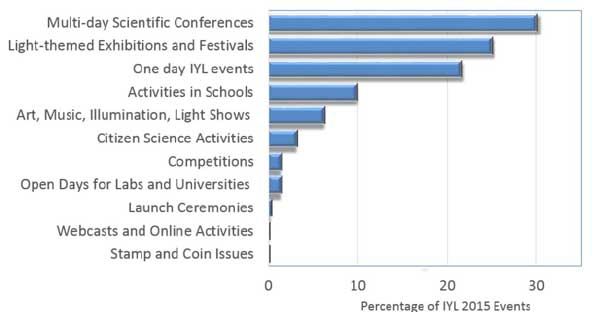

I suspect we could have a day long conversation on measuring outreach impact. Joe and I was inundated with requests for metrics, targets and KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) from 2014 onwards, but I knew that these would be completely meaningless in the context of an International Year because they are completely irrelevant to the majority of the countries of the world. One would lose an enormous amount of time trying to explain what these were all about in smaller and developing countries where it was already a huge challenge to even organise one or two events. Making event organisation bureaucratic would have turned people off. Moreover, how on Earth does one quantify the potential inspiration or positive feeling towards science that is felt by a young child … So rather than trying to invent artificial targets, we decided to simply implement a very efficient system of "global tracking" to keep track of the numbers that did mean something like attendance, fundraising, media hits etc. These numbers are summarised quite well in the Executive Summary (found here: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002460/246088e.pdf).

That said, we received a million euros to run a large EU-funded project during the International Year of Light, and here we couldn’t avoid KPIs and targets. On the other hand, it was much easier to envisage meaningful numbers and categories within the EU, and we developed a questionnaire that we used both during the event as well as afterwards (via an email request to the mailing lists).

Q. What advice would you give to others trying to outreach on a large or small scale?

In my view, it is essential not to "become a manager" but to remain actively involved in the outreach itself through meeting students and talking and engaging personally with the public. There was a huge amount of frustration and hard work with the international nature of the planning, and personally seeing the positive impact of what we were doing was essential to remain focused.

Q. Is there any part of your outreach experience you just think worth telling others about in this spotlight feature?

The International Year of Light would not have worked without scientists freely donating their time and effort. Interestingly, there were many professionals in the organising team who did not believe that there would be such volunteer enthusiasm, but having seen this myself over many years, I had no doubt that the scientific community would step up. But it was essential to be able to bring people together under a unifying banner, and this is something I would stress if anyone wanted to do something similar in the future. It can be hard to work with large international organisations, but the mandate that they give to a project allows one to do things that would not otherwise be possible.

Bureaucracy needs to be minimised to avoid stifling enthusiasm. Of course, with such a large event with many diverse and dispersed activities globally it was important to have a means of following what was going on, and oversight was needed to check events to ensure they were respecting the goals of the Year and in particular to exclude any pseudoscience.

I also noticed something that delighted and concerned me in equal measure. Of the scientists organizing activities during 2015 there were about the same number of men and women, yet data from UNESCO shows that women only make up 28% of science researchers worldwide. This suggests that perhaps a disproportionate number of women were volunteering to work on outreach during the International Year. Why this is, I am unsure, and as wonderful as it is, I wonder how outreach activities are impacting early careers in a scientific community where outreach is still not fully supported. Including outreach contributions into evaluations of career performance and promotion is something that I think is essential.

John M. Dudley, FEMTO-ST Institute and the University of Franche-Comté & Joseph J. Niemela, International Center for Theoretical Physics shared the Dwight Nicholson Award for Outreach for:

"For outstanding leadership of the International Year of Light (2015) and for optical science and engineering outreach on a global scale."

Joseph J. Niemela,

International Center for Theoretical Physics

Q. How did you get involved in outreach?

Well, if we go all the way back into prehistory, outreach for me had its tenuous beginnings at home as an undergraduate physics student trying to explain what I was doing (and why) to parents, grandparents and other curious relatives — the "taxpayers" helping to fund my education, including occasional laundry service and care packages of take-away meals. That is a particularly tough audience that won’t accept buzz words or mathematical descriptions (unless you perhaps grew up in a family of Ph.D.s and frankly, I am sure I failed miserably at least on the first few rounds. Later, as a postdoc, this became easier and I had the good fortune of being offered an opportunity to teach a university course for non-science majors-- from philosophy majors to student-athletes. This was not a popular course for the faculty, as I vaguely recall, and I had the strange feeling that they were drawing straws… something that I never quite understood because it was not only tremendously fun but also a type of honor; for me, it opened up the joys of communicating science to a wider group of people who were not intending to make a career out of physics but were anyway very curious about it. It was a new challenge that was met with many classroom demonstrations, a substantial amount of patience, and a lot of care in wording. In the front row was a young woman who was blind, accompanied by her dog. That really forced me to improve the quality and accuracy of my oral delivery (not an easy task as those who know me can attest…) particularly since the demonstrations were largely visual. She maintained a position at the top of the class despite everything. Further back in the class was one of the student-athletes. Interestingly, the athletic department called me up one day to check on him, obviously worried (panicked I would say) about his progress in a physics course of any sort and offering to provide tutors and requesting that I work with them. I was very happy to reply that while all that was appreciated, I didn’t see any need for extra help as he was there every day and was curious enough that we would occasionally discuss the subject of the day in more depth after class. So much for stereotypes….! Anyway, I learned a lot from this experience that would push me towards doing outreach later. I eagerly accepted other opportunities to engage with people I normally wouldn’t have the chance to meet, from lunch talks at rotary clubs to plenary talks at medical conventions (really I did this…it was fantastic!). And all the while, I was going once a year to my daughter’s school (from third grade through high school) with some liquid nitrogen, a bag of demonstrations, and a few jokes to make it all go smoothly. Fast forwarding, moving to a UNESCO organization (the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Trieste Italy) was like finding the holy grail of outreach; the Centre’s founding Director, the late Nobel Laureate Abdus Salam at one time asked scientists there to try to find some appropriate balance between their own fundamental research and another, perhaps more applied, area of science that addressed more immediate societal needs in developing countries. For me personally that "other" area was optics and photonics, in which I quickly found a natural avenue for doing outreach on a global scale, from the introduction of inquiry-based learning methodologies for teaching optics in collaboration with the science sector at UNESCO headquarters, to providing opportunities for hands-on experience and experimental opportunities in optics and photonics (and other areas as well) for early career scientists in developing countries — always with a particular attention to young women students and scientists. Getting sufficient funding for science is a challenge everywhere, but certain countries also have become somewhat isolated due to sanctions, war, etc. Isolation leads to a type of academic in-breeding, which we know was not good for Europe’s royalty, and neither is it good for science, which lives in open international air on a front which moves always forward. One important part of outreach in developing countries is simply showing up, providing a different perspective, if only temporarily, to young aspiring physicists in addition to specific training.

Q. What do you find most exciting about outreach? Most rewarding? Most difficult?

For me the most difficult part of outreach is also part of what makes it exciting: getting out of your comfort zone, and trying to connect in some real way, to communicate excitement, understanding, and some sense of the place of physics and physicists in society to people from all walks of life and all ages. For IYL 2015, one difficulty was of course finding time to properly do the other jobs I was actually hired to do, as this was an entirely voluntary for everyone involved.

Q. How did you happen to be put in charge of organizing the UNESCO 2015 Year of Light?

Becoming engaged in the organization of the Year of Light occurred through a number of fortunate encounters, starting in Varenna, Italy in 2011 for the EPS conference "Passion for Light" at which the Year of Light initiative was publicly announced. The organizers had sent a message to ICTP that there were some spots available for students from developing countries, and given the lineup of speakers it was a great offer indeed. I volunteered to take a couple of young women Diploma students from Africa — well I wanted to see these talks too! I happened to mention this to the Director of Basic and Engineering Sciences in UNESCO headquarters and he was delighted, mainly because the Assistant Director General for Science had wanted to come for it but had a conflicting engagement, so I was asked if I would agree to represent her in the opening ceremony. Perfect! That was a great 5 minute opportunity to describe the teacher-training program in optics and photonics shared between ICTP and UNESCO headquarters (which would become one of the important global projects during IYL 2015), as well as the SESAME synchrotron project in Jordan, which at the time had an expected commissioning date of 2015, the same year as the proposed Year of Light. There I met two wonderful people, Luisa Cifarelli, then President of EPS and John Dudley, EPS President-elect. I remember being completely awed at John’s let’s-get-straight-to work character — my hand was just cooling off from our introduction and we were already deep in discussions over details of the Year, how to get it through the UN system as well as what to do to get scientists in developing countries involved. If I were to think of some of the things I found personally rewarding in this outreach effort it was to work with outstanding professionals like John and Luisa and many many more.

Anyway, ICTP, with its long-standing advanced program in optics for early career participants from all over the developing world, in addition to its teacher-training programs in optics, made it a natural partner, especially for what one could loosely label "light for development." ICTP also had the advantage of being completely neutral, and being the head of an office that took care of external activities at ICTP, with a professional staff that agreed to volunteer their time to help make IYL 2015 a success, made it an easier decision for the IYL Steering Committee to vote on placing the Global Secretariat there. About this point: we are mostly talking about scientists volunteering their time to outreach, but big successful projects require bringing more people on board as partners besides scientists, and the administrative staff in our Secretariat worked extremely hard, not even stopping for Christmas break prior to the January 2015 Opening of the Year. This was a particular characteristic of the Year of Light: partnerships with scientists, engineers, industry leaders, artists, theologians, designers, our fantastic secretarial staff, and many others the world over, all working together to make it a success.

Joseph J. Niemela

International Center for Theoretical Physics

"Isolation leads to a type of academic in-breeding, which we know was not good for Europe’s royalty, and neither is it good for science, which lives in open international air on a front which moves always forward. One important part of outreach in developing countries is simply showing up, providing a different perspective, if only temporarily, to young aspiring physicists, in addition to specific training."

Photo: Joe Niemela

Post IYL inspired outreach at Quaid-i-Azam University

Photo: Joe Niemela

Post IYL inspired outreach at Quaid-i-Azam University

Photo: Joe Niemela

Post IYL inspired outreach at Quaid-i-Azam University

Q. How did such a global endeavor impact you?

One of the most interesting and rewarding aspects of IYL was to work with people from different areas of society. I engaged heavily with the lighting industry for instance and also with the artistic communities (light-painting, sculpture, music). We were committed to raising awareness about light-based solutions to societal problems, and I began to realize that I was one of those whose awareness was being raised, for example in areas such as lighting design and human-centric lighting where I understood that awareness raising was also associated with creating markets that enable better products to emerge for improving the quality of life of people everywhere, from off-grid villages to major metropolitan areas. The idea that philosophers and artists could play a part in what seemed at first to be a purely "scientific" year seemed strange initially, but it made a lot of sense as the year began to take off. Using the term "light" meant that each group felt like this was "their" Year and indeed it was. It was ours. And that was the magic of the Year of Light. It was an intrinsically inclusive year in a period when inclusion is fading away rapidly around the world. It was a wonderful opportunity to involve young people, from the many physics students who volunteered to help at the opening and closing ceremonies to the student chapters of major optics societies like SPIE and OSA around the globe doing their part to bridge the gap to even younger audiences. The fact that we could empower national or regional committees to act locally around the world meant that we could multiply our efforts with very little funding, noting that there was no funding coming from the United Nations for any of the activities. This had a silver lining as local committees found that they could leverage IYL 2015 to help them get funding from their own governments for local outreach events, which in turn allowed for relationship-building that would better enable them to engage in the future. One interesting note is that one of our musical collaborators, the Italian group Jalisse, winners of the San Remo Music Festival, worked this year with the Foreign Ministry and helped to make important introductions at a diplomatic level in central Asia, where we are wanting to get further involved in scientific outreach. You never know where good relationships can take you.

Q. Were there any measures made on the impact of the Year of Light? If so, what were those measures and what can be concluded by them? (Please note — I know from my personal experience the year of light was very impactful, but I am often asked this question about endeavors I am involved in and I have not done much to quantify my outreach efforts so I am curious.)

Impact is indeed a difficult quantity to measure. Most of this information is included in John’s material which involves estimating participation, financial contributions, website reads, media mentions, etc. We can only estimate of course, but the evidence points to huge numbers — a significant fraction of the world population — having contact with the Year in one way or another in many countries on all continents (including Antarctica!).

Q. What advice would you give to others trying to outreach on a large or small scale?

My advice is to just jump in. Besides the social responsibility, there are personal rewards (satisfaction comes almost immediately, transmitted from the eyes of those who are benefiting). It need not, of course, be on a global scale such as IYL 2015. Close to home is much easier and there is always an opportunity to help motivate and inspire others which comes back to benefit the scientific community sooner or later. As for global engagement, I would strongly encourage scientists to accept invitations to give talks in countries in the developing world. The experience is incomparable and those who do it keep coming back, realizing they can make a huge difference in the lives of bright and talented young students and early career scientists who may not have many opportunities to travel outside their countries. In particular, I would especially encourage US scientists to consider lecturing in Pakistan and Iran — as scientists we can help keep the doors of communication open in spite of the political rhetoric and actions which tend toward isolation. Scientists as diplomats. It is an idea that has substantial merit. Helping to train their young people, sharing your perspectives on doing science — on how to be a scientist — makes you part of the solution to important problems in our world today.

Q. Is there any part of your outreach experience you just think worth telling others about in this spotlight feature?

There is one feature of the IYL follow-up that I would like to share. I have been going to Islamabad for a number of years now having always found a warm welcome there, from scientists and ordinary citizens I meet on the street. During IYL 2015 we organized several activities there, one being the teacher-training workshop in optics and photonics, held at the National Center for Physics (modeled after the Abdus Salam ICTP). Two facts were always in my mind — Malala’s extraordinary courage to promote education for girls and the many banners I saw posted on the main boulevards of Islamabad exhorting whoever was reading them to "let girls go to school." I soon after talked to Becky Thompson at APS during a dinner at the IYL 2015 closing ceremony, a month or so later. She immediately said yes to my request for donation of special kits that could help keep kids interested in science. Soon after I arrived back in Trieste, a big box of light science kits arrived from APS, and together with the Photonics Explorer kits that were in my office we arranged a shipment to local colleagues in Islamabad and nearby Abbottabad. With these they started to arrange a series of one-day hands-on science workshops in optics for high school girls and young women undergraduates. Fantastic. Outreach that impacts hundreds of lives with only volunteer effort and donations of equipment. I attended the workshop at Quaid -i-Azam University and found 20 young women undergraduates who showed up on a university holiday, in spite of the fact that there was no credit associated with this hands-on workshop, and the fact that it was in July with an outside temperature above 40 degrees Celsius, and no air conditioning in the classroom. We had plenty of liquids to satisfy our thirst, but there was another thirst — for learning — that you rarely see anywhere. I think that it was one of the most inspiring moments of my career, to witness just how much they wanted this opportunity to get their hands on some equipment and do experiments. It is impossible to walk away from this without feeling a warm sense of accomplishment. Next stops are public schools in the remote areas northwest of Islamabad, which often do not have electricity. Always more challenges. But also more rewards.

Photo: Joe Niemela

Post IYL inspired outreach at Quaid-i-Azam University.