April Session Reports: “The Legacy of Richard Feynman”

By Alan Chodos

Richard Feynman was born in 1918, and the centennial of his birth was celebrated at the APS April Meeting with the theme “A Feynman Century.” The theme was reflected in many sessions at the meeting devoted to science. The Forum on History, however, fulfilled its mission by organizing an invited session, The Legacy of Richard Feynman, that primarily dealt with Feynman the individual.

The three speakers were Paul Halpern of the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia, John Preskill of Caltech, and Virginia Trimble of the University of California, Irvine.

Halpern is the author of the recent book, The Quantum Labyrinth, about the relationship between Feynman and his Princeton thesis advisor, John Wheeler. Halpern distilled three ways in which the careers of these two giants displayed parallel characteristics: learning by teaching, thinking in pictures, and embracing seemingly crazy ideas.

Halpern revealed that Feynman chose Princeton for graduate work because of its new cyclotron with a 50-ton magnet; Feynman wanted to be close to experimental developments. He thought he would work with Wigner, but was randomly assigned to Wheeler, only 8 years his senior, as an advisor, and the two hit it off. They collaborated on an unconventional formulation of electrodynamics that used advanced and retarded potentials and did away with the field concept in an effort to tame the infinities of quantum field theory. Although in the end it didn’t work, it was a crucial stepping stone to Feynman’s later development of his path-integral approach, to which Wheeler gave the name “sum over histories”.

Throughout their careers, Wheeler was the one who tended to come up with the crazier ideas, and used Feynman as a sounding board. Feynman was often able to extract the kernel of truth from Wheeler’s insights. Both men had a keen interest in art. Wheeler took art lessons during a sabbatical in Paris, and Feynman seriously pursued painting and especially drawing during his time at Caltech, an activity that Trimble described from a more personal perspective in her talk (see below).

Preskill overlapped for about 5 years with Feynman at Caltech in the 1980s, from 1983 when he arrived there to Feynman’s death in early 1988. In addition to his own recollections, in his talk Preskill assembled observations of and about Feynman from numerous other physicists, such as Matthew Sands, Steven Weinberg, Murray Gell-Mann, Robbie Vogt, Paul Steinhardt, Michael Turner and Sidney Coleman.

The picture that emerges is of someone who pursued his own way, without paying much attention to current fashions. For example, Feynman caused Gell-Mann great frustration, which developed over the years into mutual antagonism, with his parton model (Gell-Mann called them “put-ons”). Gell-Mann felt that Feynman had merely reformulated aspects of the quark model while deliberately refusing to call them quarks.

As described by Weinberg, Feynman could be extremely intimidating to seminar speakers. But in his lectures at Caltech, Feynman put a lot of effort into his interactions with students. Preskill described in some detail the genesis of the famed Feynman Lectures, including the anecdote that Feynman was at first reluctant to participate, until Sands told him that, as far as he knew, no great physicist had ever given a course of lectures for freshmen. That piqued Feynman’s interest and he agreed to do it.

In addition to the Feynman Lectures, over many years Feynman also gave a course for freshmen dubbed “Physics X”, in which students could ask him virtually anything and the discussion ranged widely. Conventional questions relating to derivation of formulas or homework problems were not allowed; as Steinhardt said, it had to be about “trying to understand something.” As Michael Turner recalled, “in those days [the late ‘60s] Feynman was everyone’s hero: the students and the faculty. I’m not sure who worshipped him more.” (This was not, however, true of Gell-Mann. In the Physics Today memorial issue published a year after Feynman’s death, all the contributions are hagiographic, except for that of Gell-Mann, who barely avoids speaking ill of the dead.)

Preskill devoted some time to describing Feynman’s interest in simulating physics with computers, focusing on a lecture Feynman gave at MIT in 1981 (more than 20 years after his perhaps more famous talk “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom” about the possibilities of nanotechnology). Feynman clearly foresaw the advent of quantum computers, although there is some controversy as to whether he appreciated their potentially vast improvement in computing power over classical computers.

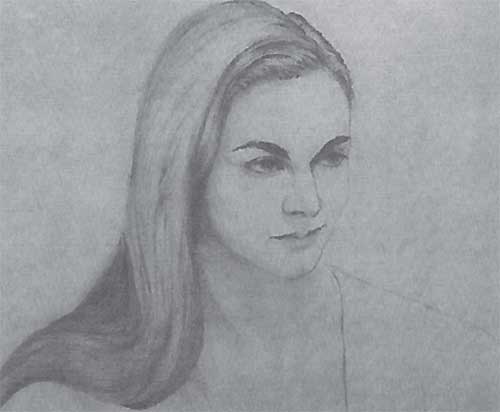

Trimble’s talk consisted of rapid-fire anecdotes that greatly entertained the audience, but to which it is difficult to do justice on the page. She enjoyed a close personal relationship with Feynman over the last 25 or so years of his life, beginning in the mid ‘60s, when Feynman was learning to draw and she, then a graduate student at Caltech (one of the very few women) was one of his models. She showed a drawing that Feynman did of her from that time, and recounted that while she was posing, Feynman would often talk non-stop, because, as she said, he didn’t like silence, and “he’d talk if you didn’t.”

Some years after Feynman’s tragic first marriage (his wife Arline died of tuberculosis shortly after their wedding), Feynman married Mary Louise Bell. It was an unhappy marriage that Trimble illustrated with the well-known Thurber cartoon from the New Yorker, in which a man approaches his house with a gigantic image of his wife lurking menacingly. By the time Trimble knew him, Feynman had undertaken a successful 3rd marriage with 2 children.

Trimble claimed that the legend of Feynman studying Spanish to prepare for a trip to Brazil is at least somewhat true, it not being clear at what point he realized his mistake. In any case, she showed some pages from books he read (in English) about the European conquest of Peru and Mexico – these were serious works of scholarship that perhaps belied the impression one gets from Feynman’s own books of a happy-go-lucky character who takes physics very seriously but not much else.

Feynman was very attractive to women, and enjoyed close relationships with many of them, but, according to Trimble, none regretted their association. (Given the large number of such liaisons documented in James Gleick’s biography of Feynman, this statement seems unlikely on purely statistical grounds).

In Trimble’s last memory of Feynman, she visited Caltech for what she thought would be a lunch date with him. She waited for him outside the room where he was giving a lecture, and could hear his voice on the other side of the door. But when the lecture ended, Feynman, in ill health, headed straight home.

She never saw him again. He succumbed soon after to the cancer that he had battled for a decade, at the age of 69.

Richard Feynman’s drawing of Virginia Trimble, sometime in the mid-1960s, when he was using her as a model.

Paul Halpern

John Preskill

The articles in this issue represent the views of their authors and are not necessarily those of the Forum or APS.