Report on the Minority Bridge Program

Theodore Hodapp

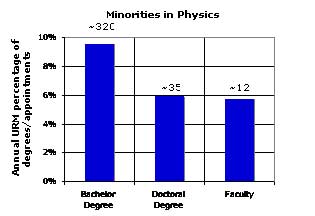

Fig. 1. Percentage of undergraduate degrees, doctoral degrees, and new academic appointments in physics each year given to under-represented minorities. All degree numbers are for US citizens or permanent residents only. Data are from the Department of Education’s IPEDS Completion Survey, and from the American Institute of Physics Statistical Research Center.

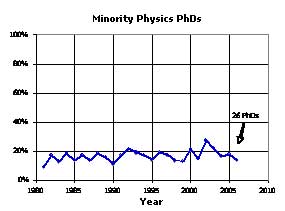

Fig. 2. The fraction of doctoral degrees given to under-represented minorities normalized to age-18 US minority population fraction. To reach parity, we must increase minority physics PhDs by about a factor of 5. Sources of this data include the US Census Bureau and the Department of Education’s IPEDS Completion Survey.

08.2 JOINT DIVERSITY STATEMENT

(Adopted by the APS Council on November 16, 2008)

To ensure a productive future for science and technology in the United States, we must make physics more inclusive. The health of physics requires talent from the broadest demographic pool. Underrepresented groups constitute a largely untapped intellectual resource and a growing segment of the U.S. population.

Therefore, we charge our membership with increasing the numbers of underrepresented minorities in physics in the pipeline and in all professional ranks, with becoming aware of barriers to implementing this change, and with taking an active role in organizational and institutional efforts to bring about such change. We call upon legislators, administrators, and managers at all levels to enact policies and promote budgets that will foster greater diversity in physics. We call upon employers to pursue recruitment, retention, and promotion of underrepresented minority physicists at all ranks and to create a work environment that encourages inclusion. We call upon the physics community as a whole to work collectively to bring greater diversity wherever physicists are educated or employed.

Physics education provides a unique look at the world, the capability to solve a wide range of problems, and the tools for success in diverse careers. Unfortunately, we as a community do a rather poor job at providing this opportunity to large segments of the population of the United States. Progress has been made in encouraging women to study physics, and the number of women pursuing advanced degrees in physics continues to climb linearly (increasing steadily over the past 4 decades at about 0.4% per year, although still far short of parity) but our progress with underrepresented minorities (URMs) remains poor. For our purposes we include as URMs African-, Hispanic-, and Native-Americans. African-Americans as a group have, in fact, lost ground in the past decade in both absolute numbers and in their representation as a proportion of the US population. To continue to advance the field of physics, to take advantage of the benefits of diversity in solving problems, and to provide everyone the opportunity for a 21st century caliber education, we must address this issue.

Underrepresented minorities make up about a quarter of students entering college in the US, but only about 10% of physics bachelor’s degree recipients (a drop of a factor of 2.5), and the leak continues by another factor of almost two when we look at doctoral degrees in physics. Figure 1 indicates the percentage along with typical annual numbers at each stage.

One positive indicator is that at least in the transition to academia, the fraction of URMs relative to the overall population remains roughly equivalent to the production of new PhDs, with about 10 individuals each year choosing this route.

Additionally, the number of PhDs granted to minorities in physics has not seen any appreciable increase in nearly three decades.

Figure 2 indicates the percentage of physics PhDs granted to US citizens who are African-, Hispanic-, or Native-American. The number is normalized to the population fraction of 18 year olds (as the Hispanic population of the US has been growing dramatically during this period). Consequently, 100% on this scale would represent a third of all degrees granted to minorities, since that is the representation of URMs in the US population.

To address these issues, the APS Education and Diversity Department convened a series of roundtable discussion in 2008 and 2009 between the APS, the National Society of Hispanic Physicists (NSHP), the National Society of Black Physicists (NSBP), and the American Association of Physics Teachers to identify the most pressing issues facing the physics community in minority education, and what specific actions might be taken to address them.

The first result was the development of a joint diversity statement (see sidebar), endorsed by the APS, NSHP, and NSBP, which calls for action on these issues and serves as a starting point to direct our activities. Wendell Hill from the University of Maryland, a member of the APS Executive Board at the time and a former board member of NSBP, charged the APS with developing proactive strategies to address the lack of diversity in physics. The American Physical Society already has a number of programs designed to increase diversity in physics such as the Minority Scholars Program which provides merit-based scholarships to promising minority high school students and beginning physics majors, minority speaker travel grants and an active database of minority speakers. To build on these efforts, and to answer the charge, APS entered into a number of discussions throughout 2008 and 2009 to determine an appropriate set of actions. The result of these conversations has led us to initiate the APS Minority Bridge Program.

The Minority Bridge Program (MBP) has an ambitious goal of bringing the fraction of physics PhDs granted to minorities into parity with the fraction of bachelor degrees (~10%). This will require us to roughly double the rate at which these PhDs are educated (an additional 30 PhDs each year). We think this is both challenging and possible.

To get the program started, the National Science Foundation awarded the APS in August 2009 a pilot grant of roughly $130,000 to bring together many key players in the community to formulate a plan for addressing the disparity. The result has been a productive year engaged in discussions with minority students, faculty from minority serving institutions, leaders of existing bridge programs, and representatives from research universities. We have visited about a dozen minority serving institutions, made direct contact with many of their students and faculty, and brought together some of the top research universities that are eager to commit their own resources to addressing the problem.

We have seen a number of successful potential models including the Fisk-Vanderbilt bridge program the Columbia Bridge to the PhD and a number of efforts funded by the NSF’s Alliances for Graduate Education and the Professoriate. We hope to build on the successes of APS’ role in managing the PhysTEC project, in organizing discussions between Directors of Graduate Studies, and in gathering leaders of REU programs to build a program, raise funds, and actually resolve the gap between bachelor and doctoral degrees in physics for under-represented groups.

In the summer of 2010 we will hold a gathering of these groups to solidify plans and commitments and formulate an action plan. APS staff, including Michelle Iacoletti who was hired by the project, and Arlene Modeste Knowles of the Education and Diversity Department, have been working with a Steering Committee led by Cherry Murray (2009 APS President) to develop and carry out the project.

Stay tuned!

Theodore Hodapp is the APS Director of Education and Diversity.

Disclaimer - The articles and opinion pieces found in this issue of the APS Forum on Education Newsletter are not peer refereed and represent solely the views of the authors and not necessarily the views of the APS.